I was in the fifth grade when Andy Warhol held his first solo painting exhibit in 1962. He was showing his set of 32 Campbell’s soup cans. The exhibit bombed. Pop art was just getting started in the early ‘60s. Art critics didn’t get him or his art.

But he did sell five cans. One of the buyers was Dennis Hopper. Hopper was in some great Hollywood films, including “Apocalypse Now” (1979) directed by the great Francis Ford Coppola. He was also in two films I liked much better: “Easy Rider” (1969) and the superb “Giant” (1956).

Hopper specialized in playing offbeat characters. It was entirely fitting that he appreciated the sly ironic art of Warhol, an off-kilter personality in his own right. Hopper owned the painting for about five minutes. He sold it right back to Irving Blum, one of the owners of the gallery, who wanted to keep the set together. Blum then bought the complete set from Warhol for $1,000. In 1996, the Museum of Modern Art bought the 32 paintings from Blum for upwards of $15 million.

Get Early Investing into your inbox

Become a smarter investor in startups, crypto and cannabis by subscribing to our FREE newsletter filled with market research, trends and expert analysis.

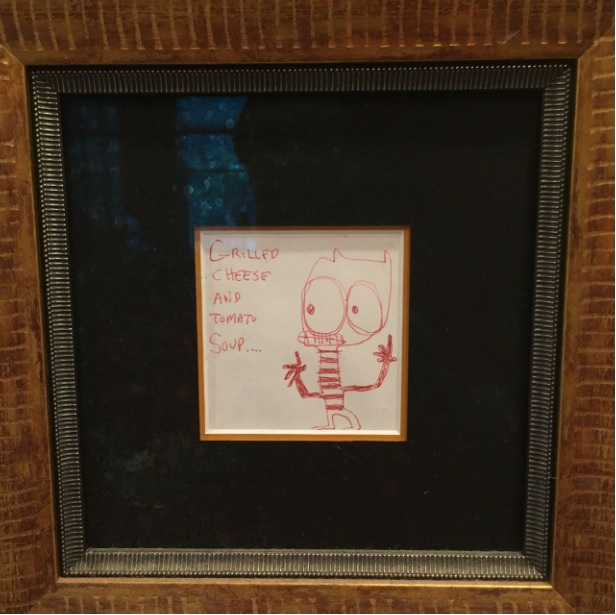

As I grew older, Warhol grew famous. And his paintings were highly sought after. Museums bought them. Wealthy private collectors bought them. I couldn’t, of course. But his Campbell’s soup cans made an impression on me. So I bought my own soup-inspired art. It’s been hanging on my kitchen wall for the past 10 years.

This is what I like: tomato soup, anyone?

Warhol’s biggest collection resides in the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

My wife Cecily and I visited the museum for the first time a few years ago. I saw my share of Warhol’s famous series of Marilyn Monroe portraits, which were made using a screen-printing technique he developed. They were all based on an image taken from one of Monroe’s more forgettable films, “Niagara,” from 1953.

I liked Warhol before the visit. But I liked him a lot more after the visit. For one thing, I learned more about his personal story, including why he chose Campbell’s soup cans to be subjects of his paintings. He had it every day for lunch for almost 20 years. And it reminded him of his mother.

As for his fascination with Monroe, not much is known. My wife asked one of the Pittsburgh museum guides about this, but she couldn’t say. But I think I have an explanation. Here’s a quote from a 1980 interview with Warhol:

My first experiments with screens were heads of Troy Donahue and Warren Beatty, and then when Marilyn Monroe happened to die that month, I got the idea to make screens of her beautiful face — the first Marilyns.

By the time of her death, Monroe’s “beautiful face” was as well known as her tragic story. Both factors, I imagine, played into Warhol’s choice.

One of Warhol’s Monroe portraits recently made headlines. His 1964 “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn” sold for about $195 million at Christie’s in New York. It’s the highest price achieved for any American work of art at an auction.

The proceeds are going to the charitable foundation belonging to the estate of the Swiss dealers Thomas and Doris Ammann. They bought it from the media mogul S.I. Newhouse Jr. in 1998 for an unknown price. That same year, Newhouse purchased Warhol’s “Orange Marilyn” (1964) at Sotheby’s for $17.3 million.

This is heady stuff — the famous artworks of famous artists selling for hundreds of millions of dollars. It used to be a playground where only the very wealthy were allowed to cavort.

But not anymore. The opportunity to own a piece of art — even very famous and expensive pieces — is becoming available to the not so wealthy. Masterworks, for example, has a Monroe (reversal series) in its portfolio. When I was meeting with Masterworks’ founder a few years ago, he mentioned this upcoming acquisition to me. Masterworks allows you to buy fractional shares in individual pieces of art, making them affordable for the casual investor or collector.

As it turned out, I didn’t invest. But the mere prospect of having a chance to invest in an iconic piece of art was enthralling in a way that investing in a startup wasn’t (through no fault of startups). You’re investing in something thrillingly tangible but also thrillingly intangible — a piece of art and also a piece of art history.

Startup investors should think of it as investing in a nearly indestructible brand. The prices of these iconic assets generally go in only one direction over time. And that’s up.

Even the most rarefied nooks and crannies of the art world are coming to us. Picasso? Basquiat? Monet? Yep, this is now retail investor territory. And amazingly, there are no “keep off the grass” signs in sight.